Elgin Blackfriars

The Order of Friars Preachers, commonly called the Dominican Order, was founded in 1215/6 by Dominic de Guzmán (Saint Dominic) at Toulouse. Since their inception, the Order has consisted of Friars and Nuns, and both single and married Laity who are known as Tertiaries or Lay Dominicans. The Order was established to preach Gospel Truth and Theological Order in the face of threats being presented to the Church by a number of heresies, particularly the teachings of the Cathar movements.

The first members of the Order to come to Britain arrived in 1221 at the instruction of the Second General Chapter held at Bologna and presided over by St Dominic himself. The Chapter sent a party of thirteen, led by an Englishman,

On 15 August 1221, very soon after their arrival in this country, the Order of Preachers established an important presence in Oxford and the headquarters of the English Province was for many years located at Blackfriars Hall in St Giles. They probably opened their teaching schools very soon after arriving in Oxford.B1

In Scotland, the first reference we have recording the arrival of the Dominican Order is an entry in the Chronicle kept by the Cistercians at Melrose Abbey. It reads, "At this time was the first entrance into Scotland of the Jacobin friars, and of the monks De Valle Olerum" [Valliscaulian Order].1

Walter Bower, the Augustinian Abbot of Inchcolm and author of the

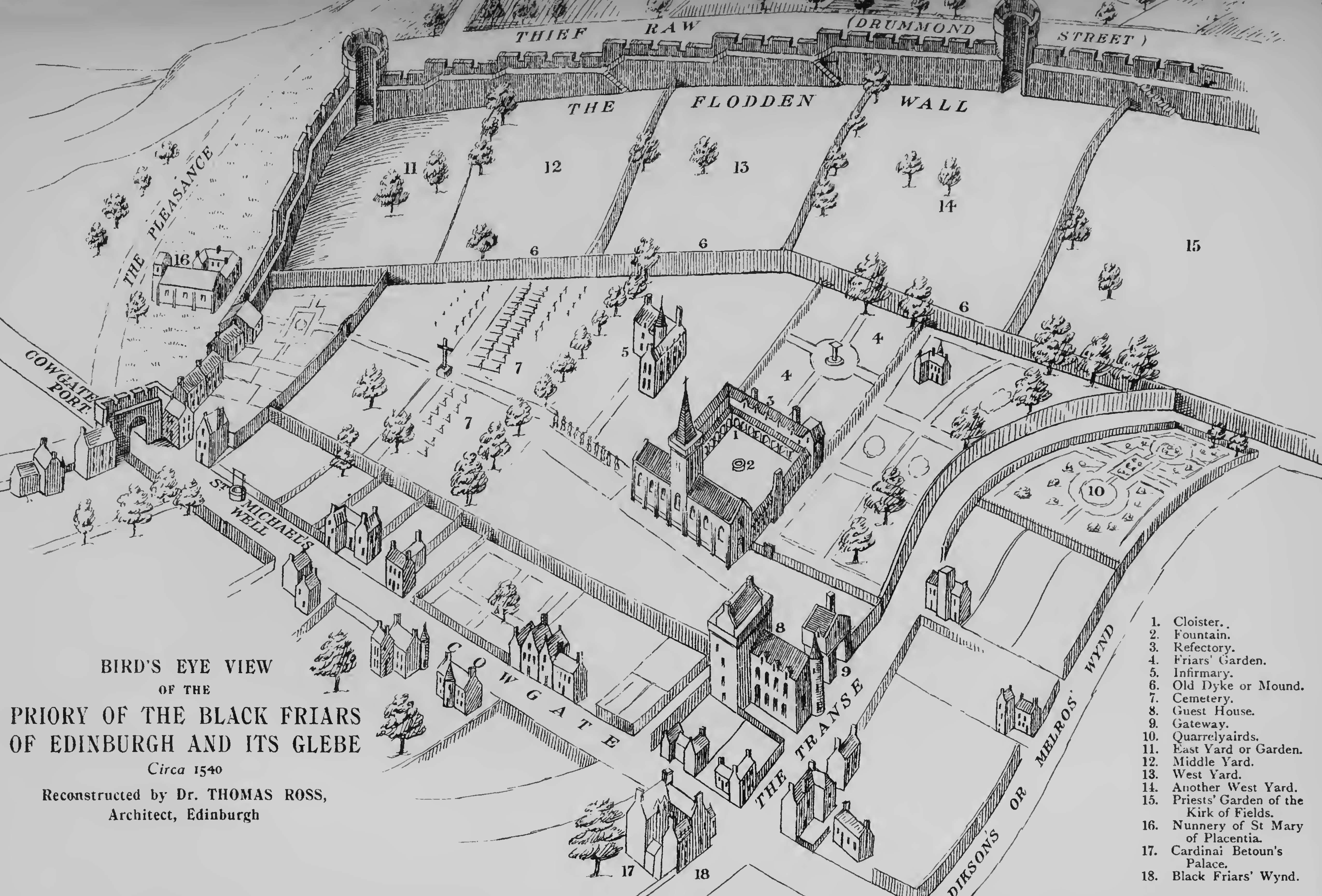

(From Bryce (1911), facing page 48)

At first, the Scottish houses were administratively part of the English Province of the Order, altough they existed as a quasi-independent Vicariate. In 1481, at the petition of King James III., the Dominican General Chapter created a Scottish Province. Sixteen Scottish Dominican houses are found in the historical record to have existed at some point in time and they are listed below, although some historians would not include the houses at Berwick or Cupar, and Haddington, certainly, had a very short 'career'.3

| Name | Fnd. → Ext. | Dedication |

|---|---|---|

| Aberdeen | 1230-49→1560 | St John the Baptist |

| Ayr | c.1242→1567 | St Katherine |

| Berwick | 1240/1→1539 | St Peter Martyr of Milan |

| Cupar | 1348→1519 | St Catherine of Alexandria |

| Dundee | c.1521→1567 | (Not recorded.) |

| Edinburgh | 1230→1566 | Assumption of B.V.M. |

| Elgin | 1233/4→1570 | St James |

| Glasgow | 1246→1566 | St John the Evangelist |

| Haddington | 1471→1489 | (Not recorded.) |

| Inverness | 1240→1566 | St Bartholomew |

| Montrose | 1275→1570 | Nativity of B.V.M. |

| Perth | 1240→1569 | St Andrew |

| St Andrews | 1464→1559 | Assumption & Coronation of B.V.M. |

| St Monan's | 1471→1557 | St Monan |

| Stirling | 1249→1567 | St Laurence |

| Wigtown | 1267→1560 | Annunciation of B.V.M. |

| Supposed Foundations | Notes | |

| Coupar Angus | Fictitious - based on spurious charters. | |

| Crail | No reliable evidence. | |

| Dumfries | This entry is erroneous. | |

| Dysart | No reliable evidence to be found. | |

| Forres | Evidence almost entirely wanting - so rejected. | |

| Inverkeithing | Existence is by no means conclusive. | |

| Jedburgh | Name Blackfriars used locally but inaccurately. | |

| Kinghorn | Based on one spurious charter - so rejected. | |

| Kirkcudbright | Reference in 1512 is an error for Greyfriars. | |

| Linlithgow | Existence for a brief period cannot be ruled out. | |

| St Ninian's | An error for St Monan's. | |

| Selkirk | Based on a charter whose authenticity is questionable. | Table Source: Cowan & Easson (1976), p. 116-123. |

"Mendicant tradition seems to have appealed very much to King Alexander II’s personal piety and devotional tastes."4 However, it would not be true to say that Alexander's motives were merely 'popularist' - that he hoped to gain from an association with an Order which was rapidly gaining the support of the populace. It would be more fair to ascribe his motivation to the pro anima purpose of much of his religious patronage. However, his evident approval of the Dominicans and their obvious purpose - to provide sound teaching to the urban populace - encouraged many others to become benefactors. This close association between the Crown and the Order was to be of vital importance to the Dominicans for some 300 years.

An interesting fact which may be gleaned from the table above is that, apart from Aberdeen (whose foundation date is uncertain), Elgin (1233) was certainly the third Scottish house to be founded after Edinburgh (1230), and possibly the second. It pre-dates even Stirling (1240) and Perth (1240). It is tempting to suggest that this clearly demonstrates King Alexander II (Alaxandair mac Uilliam)'s personal interest, both in furthering the work of the Order and in developing the Royal Burgh of Elgin itself.

Although his son, King Alexander III., Alaxandair mac Alaxandair (1249-1286), continued in the footsteps of his father, it would appear that his personal religious convictions were more in keeping with the Franciscan Order. But royal favour was still shown to the Blackfriars and a number of the nobility added to this largesse. Devorguilla, lady of Galloway, instituted a Dominican house at Wigtown c.1267 and, in 1348, Duncan, earl of Fife, supplicated that the Pope would allow him to build a house at Cupar, although it was never a substantial establishment.

From the Rotuli Scotiæ, Vol. I., p. 29, we learn that on the 7th March 1297, Edward I. issued a writ to the Earl of Surrey to examine the rent rolls of Aberdeen, Elgin, Inverness, and seven other royal burghs, in order to ascertain the amount of stipend paid by Alexander III. and Baliol, to the monasteries of Black Friars at these places, with the strict injunction to continue the payment of the same from the Crown revenues of these towns.4a

One surprise in the history of the Scottish Dominicans is that there was not a house of the Order in St Andrews until c.1464 and it was then only a very small establishment of perhaps only two or three friars. It was only in c.1518 that a significant expansion was carried out. It is believed that the instigator for this was Bishop James Kennedy (1440-1465) who also founded St Salvator's College in the University. Kennedy was determined to improve the 'education' of the priests within his diocese and he no doubt saw in the Dominicans an opportuity to help him accomplish this aim, making use of the Order's famous abilities both as students and teachers. Of course, when St Andrews was raised to 'metropolitan' status on 17th August 1472 this became an even more important ambition for the first archbishops. William Elphinstone, Bishop of Aberdeen, had been nominated to succeed to the archepiscopal see of St Andrews but he died in October of 1514 before he could be translated. However, his substantial wealth was, in part, given to finance the building of a Dominican convent within the University. Richard Oram writes that, "Elphinstone, the founder of the University of Aberdeen and an active promoter of clerical education within his diocese, was here clearly identifying the Dominicans and their revived reputation as a learned order as standing at the forefront of efforts to drive up the quality of education within the clergy."5

One of the most celebrated of the Scottish houses was that which had been built at Perth. It had gradually inherited more and more of the lands which had once belonged to the old Royal Castle there, and successive Kings added substantial royal appartments to the friary buildings. These were not only lodging-houses for the royal family but were also sufficiently commodious to accommodate visitng foreign 'missions' and, for a considerable period, most of the Parliaments of Scotland were held here also.

In 1559, a mob went on the rampage in Edinburgh and the house of both the Black Friars and the Grey Friars were sacked. At the Reformation a settlement was made, which offered the remaining friars a pension of £16 on condition that they lived out the rest of their lives 'quietly.' Some went abroad, others became ministers of the new Kirk, while some continued to minister as best they could to the remaining adherents to the Catholic faith, often in secrecy and in hiding. For a while, Mary, Queen of Scots, continued to have two Dominicans at Holyrood, whom she supported as best she could. One of them, John Black, was murdered on the same night in 1566 as the Queen's Secretary, David Riccio. The other, John Craig, took a very different path and ultimately became minister of the High Kirk of St Giles in the town. After 1600, a number of Irish Dominicans were still to be found ministering in the Western Isles, and there were also some Scots who chose to live abroad permanently as Dominican friars. We should also remember here that there continued a 'hard-core' of individuals who worked strenuously to bring Dominicans back to our Scottish lands. One such person was Patrick Primrose, an Edinburgh graduate in law, who became a Dominican and laboured long and hard to bring the Order back to our shores.

The House of the Dominican Friars - Elgin (St James).

As we have seen, the Order of Friars Preachers had a house in Elgin from the first half of the thirteenth century - it is thought to have been founded between 1233 and 1235.6 The foundation is ascribed to King Alexander II. who apparently granted certain 'redundant' castle lands, which lay to the north of the Castle Hill (now Lady Hill), to the Order. There is a parallel here with the Blackfriars at Perth whose house was located on similarly redundant land which had once belonged to the Royal castle. The house was certainly in existence by 1285 in which year, on 29 March, 'five chalders of victual' are recorded as having been granted to the friars there by King Alexander III.7

On 17 November, 1520, the revenues of the Maison Dieu in Elgin were granted to the Dominicans and this act was confirmed by the Pope (Leo X) on 21 June 1521.8 However, the Dominican's possession was in dispute before 21 December 1526 when the guardian of the house petitioned the Pope claiming that he had been 'deprived' and violent hands had been laid upon him by Patrick Dunbar, succentor of Moray.9 A general confirmation of previous donations was granted by the crown on 9 October 155110 and thereafter there are few historical references to the house of Blackfriars.

A small community which remained in the house at the Reformation was probably disbanded when the lands and revenues appear to have been gifted to the Dunbar family, one of whom, Alexander Dunbar, Dean of Moray, received crown confirmation of his feu on 7 January 1570/1.11 Property belonging to the Blackfriars was also granted under the Great Seal on 4 March 1573/4 and 9 January 1575/6.12

The precise location of the Dominican Friary in Elgin has been a matter of sometimes intense debate. The central problem is the lack of archaeological evidence, but the matter has not been helped by a certain lack of 'enthusiasm' on the part of the researchers who have been involved. I believe that a significant opportunity has been missed in recent times when determining the 'fines studiorum' (limits of study) of an extensive programme of excavation which was carried out on the Castle Hill (Lady Hill). The friary was located so close to the northern flanks of the Hill that it would have been appropriate to extend the work northwards and to make a concerted effort to search for any remains and so 'plug the gap' that surrounds this most important episode in Elgin's history.

Hall, (et al), writing in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, become quite vague when they come to the subject of the Blackfriars.X5 They state that, "Wood's map of Elgin in 1822 shows only two buildings by the Lossie on Blackfriars' land, which are not specifically identified as part of the Blackfriars' monastery, and are unlikely to be the buildings recollected." This is correct but it was never likely that the Blackfriars' building would be shown on a map which was produced at a time when these lands are known to have been converted to use as a 'nursery/garden'. If reference had been made to Pont's map of Elgin and northeast Moray which is dated to ca.1583-9, only a little time after the Blackfriars' buildings had been vacated, then they may have noticed an interesting feature (building) shown lying between the Castle and the Cathedral, a little towards the river (see map below).

NLS Shelfmark Adv.MS.70.2.10 (Gordon 23)

On close inspection, the building which Pont drew does not appear to be part of the Castle complex and he showed it lying a little further north-east, towards the River Lossie. The building's position does not correspond to any known part of the Castle and it appears to be quite 'substantial'. It was obviously a building of some importance - otherwise Pont would not have noted it - and, through the course of history, there has not been any other building at this location except the Dominican Friary. Hall (et al) make the following comment -

"The Blackfriars' stank was a well-known local feature, sometimes mentioned in property deeds, and is thought to have been located in excavations in 1971 when a number of skeletons were discovered. If the monastery was located south of the stank found in 1971, then it must have been very near to the castle; alternatively, and perhaps more likely, the feature found in 1971 was not the Blackfriars' stank."X10

It would appear that Hall's team felt that such a close proximity to the castle was something that should make us disbelieve that the friary was at this location. A closer inspection of the position of the building of the Perth Blackfriars would confirm that such a position for the Elgin house was not at all unacceptable.

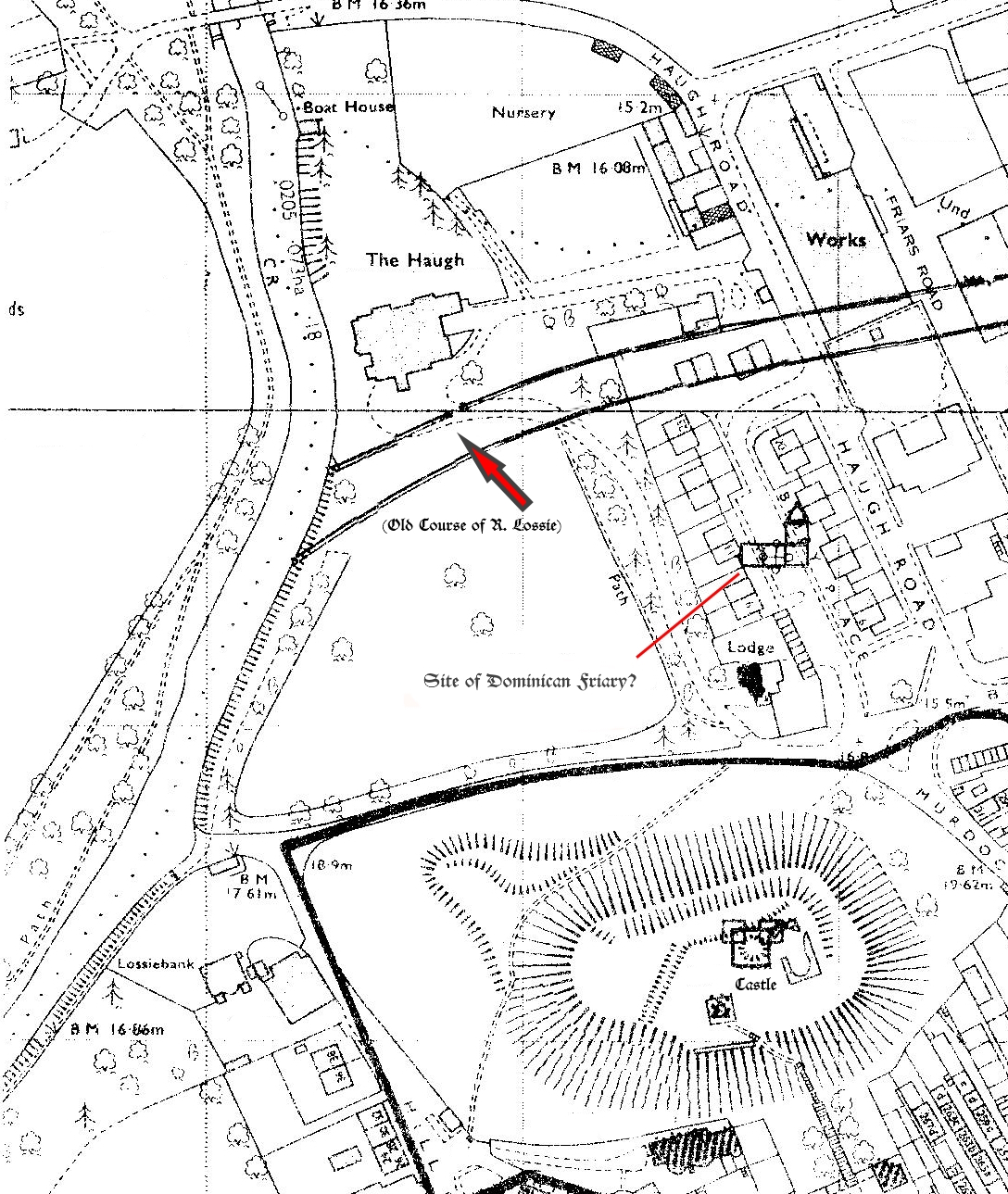

The site of the Friary complex is marked on certain Ordnance Survey maps at a location which corresponds to a Grid Reference

The Friary would appear to have been a substantial collection of buildings. Mention made of them in the seventeenth century refer to the property as consisting of a manor place, houses, biggins, yards, orchards, etc., but no trace of this 'complex' has ever been found. Simpson & Stevenson comment that, "Excavations within the last ten years have recovered from the reputed site of the Dominican Friary stank (NJ 212 629) a number of skeletons." They continue, "It is not possible to positively identify this burial ground with that of the Friary, especially as the excavator considers the date of deposition to be seventeenth century. However, there is no reason why the Friar's cemetery could not have continued in use after the Reformation."17 The former Blackfriars' cemetery in Perth was reused after the Reformation for the burial of plague victims.17a There are unconfirmed traditions that some of the gravestones from the Elgin site were used as building materials for houses at Bishop Mill in 1750.18

The present author believes that we should remember where the old course of the River Lossie ran - the stank being a remnant of it (an oxbow lake). I have a personal memory, from the 1960's, that the 'undercroft' of the stage which was part of the recently constructed Church Hall of Holy Trinity episcopal church, at the foot of North Street, had to be fitted with a sump and a powerful electric pump with a float-switch. The Hall had been built directly over the old course of the River Lossie and frequently flooded when the level of the Lossie rose and water permeated along the previous river-course. I believe that the idea of a cemetery in such a frequently flooded area as the Blackfriars Stank is questionable, to say the least. Any cemetery (and indeed the Friary buildings themselves) would have been located on higher ground within the priory policies. The idea of the dead lying in flood-water would have been anathema. However, in later times it is quite possible that plague victims were hastily deposited in the stank in the hope that they would sink and no longer be an infection risk. When the bodies were discovered there were no associated finds of either coffins or coffin-nails which would indicate that the bodies had been simply wrapped in shrouds - so as to sink more easily?

The proprietor of the Mansion House Hotel, which today occupies the building once known as the Haugh has told me that they have cellars which are liable to flooding when the river is high, in a similar manner to Holy Trinity's church hall.19 The old course of the river runs just to the south of the hotel. Within Simpson & and Stevenson's work, there is a useful map which is derived from the Ordnance Survey.20

Based on the Ordnance Survey (1978) 1:2500 Plan NJ 2162.

From Simpson & Stevenson (1982), based on the Ordnance Survey (1978) 1:2500 Plan NJ 2162.

To return to the matter of the buildings of the friary, we have only the description given previously to assist us - that they comprised "a manor place, houses, biggins, yards, orchards, etc.." In the total absence of reliable archaeology, the only avenues for research left available are to make a study of the other friaries in both Scotland and England, and to search the constitutions of the Order in order to find any evidence of guidance being given about friary buildings by the General Chapter.

Bede Jarrett considered that, "The definite form taken by a Dominican priory in pre-Reformation days can be reconstructed with almost absolute accuracy,"20b and, going by the dictates of the General Council of the Order, this should indeed have been so. However, even a cursory survey of the Scottish friaries leads to a conclusion that there were, in fact, many 'varieties on a theme' and the remains which exist in England clearly demonstrate that, even on fairly fundamental issues such as the relative locations of the Nave of the priory church and the friar's Cloister, there is little consistency. The cloister is sometimes attached to the north of the nave, most often to the south, but also occasionally at a distance from the church.21 The only consistency here is that every friary had a cloister and a church. The other required buildings are a refectory, a dormitory, study areas (which could be in the cloister or the dormitory), a chapter house, and a library. Some friaries also had subsidiary buildings such as an infirmary, and a guest hall, and there would have been a need for buildings in which the Lay members could carry out their daily work. The friary always had its own cemetery which, on occasion, doubled as a preaching place when the 'audience' was too large for the nave of the church. Finally, the friary was always most concerned to secure a good source of drinking-water which either meant a well, or a culvert leading from a nearby stream or river.

It is believed that the official transumpt of the Register belonging to the Dominican Priory of Elgin is preserved in the Advocates Library.22

1560 (6th July) - on this day, at Kilravock, "it is appoyntit … betuix honorable pertsones, viz., Huchone Rois of Kilrawok on the ane part, and Jmes Innes broder german to ane honorable man William Innes of that ilk, in manner, form, and effect as eftir followis; that is to say, the said James sall, Godvilling, marrie and to marrage hawe Mariorie Rois, doychtir to the said Huchon Rois of Kilrawak; for the quhilk mariage the said Huchon sall content and thankfullie pay to the said James Innes, the sovm of four hundreth and fiftie merkis vsuall monye of Scotland … Innes to infeft her in Over Manbeins and Neder Manbeins, the quhilks he halds of few of the Black Freiris of Elgyne …"23

A1. Hinnebusch (1951), p. 3., n. 7. "The first four friars sent to Spain in 1217 were Spaniards. Among the seven sent to Paris, were four Frenchmen. In 1219 Simon of Sweden and Nicholas of Lund, both of whom had entered the Order at Bologna, were sent to Sweden; and in 1222 Salmon, whose birthplace was Aarhus in Jutland, made the first foundation in Denmark." Return to Text

B1. Hinnebusch (1951), p. 9. "Legally each Dominican priory was also a school. Even the earliest Constitutions of the Order prescribed that no priory should be constituted without a lecturer in theology." Return to Text

1. Chron. Mel. p. 59, under the year 1230. The name 'Jacobins' is the nickname that was given to the Dominican Order in the Middle Ages in France. Their first convent in Paris was located in the rue Saint-Jacques, (Latin Jacobus), and that name came to be attached to the order itself. Return to Text

2. Scotichronicon, vol. 5, 145. Return to Text

3. Cowan & Easson (1976), p. 116. Return to Text

4. Oram (2021), p. 114; Oram (2012), 213-223. Return to Text

4a. Rotuli Scotiæ, Vol. 1., p.133. Return to Text

5. Oram (2021), p. 129. Return to Text

6. Simpson & Stevenson (1982), p. 30. Return to Text

7. Cowan & Easson (1976), p. 118; R.M.S., i., no. 245. Return to Text

8. Cowan & Easson (1976), p. 118; Reg. Supp., 1744, fos. 192-192v. Return to Text

9. Cowan & Easson (1976), p. 118; Reg. Supp., 1914, fos. 207v-208v; 1915, fo. 56; 1918, fos. 206-6. Return to Text

10. R.M.S., iv., no. 638. Return to Text

11. R.M.S., iv., no. 1955. Return to Text

12. R.M.S., iv., nos. 2189, 2485. Return to Text

X5. Hall, D. (et al) (1999), p. 816-817. Return to Text

X10.Hall, D. (et al) (1999), p. 817. {DNS: A 'stank' is a pond, pool, small semi-stagnant sheet of water, especially one that is overgrown and half solid with vegetation. OR a ditch, an open water-course, often applied to a part of a drainage system.} Return to Text

13. Wood's Map of Elgin, dated 1822, shows the land of the Blackfriars being occupied by "Mr. Grigor" who was using it for the purposes of running a nursery. His nursery land is shown lying between the Blackfriars' Haugh to the west and the Glebe to the east. The map also shows "the Supposed former Course of [the] Lossie," lying to the north of the Blackfriars. It was this Mr. Grigor who built the first mansion, kown as "the Haugh", on these lands. Return to Text

14. Mackintosh (1914), p. 180. Return to Text

15. Mackintosh (1914), p. 133. Return to Text

16. Simpson & Stevenson (1982), p. 31. Return to Text

17. Simpson & Stevenson (1982), p. 31, (making reference to p. 16). Approximately 50 skeletons were discovered and it has been suggested that they were to be dated to the seventeenth century and were possibly 'plague' victims. Return to Text

17a. NSA 1845, 36.

18. Mackintosh (1914), p. 180. Return to Text

19. Personal communication with Mr. Khawar Lateef, of the Mansion House Hotel, The Haugh, Elgin, (15 August 2023). Return to Text

20. Simpson & Stevenson (1982), Map 3., (endnotes). Return to Text

20b. Jarrett (1921)), p. 24. Return to Text

21 At Cardiff the cloister was to the north, Edinburgh to the south, whilst at Norwich, the cloister and the church were separated by a small open court. Return to Text

22. Bryce (1982), p.7, (footnote 1). The register referred to is now in the Collections of the National Library of Scotland [Adv.MS.34.7.2. https://view.nls.uk/mirador/217320023] Return to Text

23. Innes (1848), pp. 229-230. [These are the lands of Upper and Lower Manbeen which lie on the west bank of the River Lossie, SW of Elgin and this extract shows that the Black Friars of Elgin had them feued to Hugh Rose of Kilravock at this date (1560).] Return to Text

Bower, Walter, (1385-1449) Scotichronicon: new edition in Latin and English with notes and indexes, (ed.) D.E.R. Watt and others, 9 volumes. Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press (1987). [Scotichronicon]

Bryce, William Moir, (1911) The Black Friars of Edinburgh", Edinburgh: Constable.

Cowan, I. & Easson, D. (1976) Medieval Religious Houses, Scotland, London: Longman. https://archive.org/details/medievalreligiou0000cowa/page/n5/mode/2up (accessed 14/08/2023)

Hinnebusch, W.A. (1951) The Early English Friars Preachers, Rome: ad S. Sabinae.

Hall, D., MacDonald, A. D. S., Perry, D. R., Terry, J., Cox, A., Crowley, N., Ellis, B. M. A., Holmes, N. M. M., Smith, C. and Stevenson, R. (1999) “The archaeology of Elgin: excavations on Ladyhill and in the High Street, with an overview of the archaeology of the burgh”, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 128, pp. 753-829. http://soas.is.ed.ac.uk/index.php/psas/article/view/10027

Innes, C. (1848) A Genealogical Deduction of the Family of Rose of Kilravock, Edinburgh: for the Spalding Club.

Jarrett, Bede (1921) The English Dominicans, London: Burns, Oates and Washbourne, Ltd.. https://archive.org/details/englishdominican01jarr/page/n7/mode/2up

Mackintosh, H.B. (1914) Elgin Past and Present: a Historical Guide, Elgin: J.D. Yeadon. https://archive.org/details/elginpastpresent00mack

NSA 1845, 'Perth', by Rev. Dr. William Thomson, The New Statistical Account of Scotland, vol 10, Perthshire, 1-142. Edinburgh. https://stataccscot.edina.ac.uk/static/statacc/dist/viewer/nsa-vol10-Parish_record_for_Perth_in_the_county_of_Perth_in_volume_10_of_account_2

Oram, R. (2012) Alexander II, King of Scots 1214-1249, Edinburgh: Birlinn, Ltd.

Oram, R. (2021) 'The Dominicans in Scotland, 1230-1560,' in E.M. Giraud & J.C. Linde (eds.) A Companion to the English Dominican Province: From its Beginnings to the Reformation. Companions to the Christian Tradition, 97. Leiden: Brill. pp. 112-137. href="https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004446229_005 (accessed 18/08/2023)

Simpson, A.T. & Stevenson, S. (1982) Scottish Burgh Survey: Historic Elgin, the Archaeological Implications of Development, Department of Archaeology Glasgow University.

Stevenson, D. (1987) 'The burghs and the Scottish Revolution', in M. Lynch (ed.) (1987) The Early Modern Town in Scotland, London: Croom Helm, p. 167-191.

Stevenson, J. (trans.) A Medieval Chronicle of Scotland: The Chronicle of Melrose, Facsimile reprint 1991 by Llanerch Press. [Chron. Mel.]

Rotuli Scotiæ in Turri Londonensi et in Domo Capitulari Westmonasteriensi Asservati, Volume 1, Great Britain, Record Commission. London : Printed by command of His Majesty King George III. in pursuance of an address of the House of Commons of Great Britain. [Rotuli Scotiæ, 1] https://ia601000.us.archive.org/28/items/RotuliScotiaeVolume1/RotuliScotiae1.pdf (accessed 07/09/2023)

e-mail: admin@cushnieent.com