Elgin Deanery

Hospital of St Nicholas on Spey

Hospital : OS Ref: NGR NJ 302510 H.E.S. No: NJ35SW 4 Dedication: St Nicholas

Lachlan Shaw narrated that, "The hard inhabitants of ancient times found the river [Spey] almost everywhere fordable."1 This observation was made of the river in its lower reaches, towards the parish of Bellie. However, although seldom a raging torrent, the river has presented a serious obstacle to the traveller from time immemorial and, even in the modern era, a number of unwary fishermen have come to grief in its waters!

However, the Spey was the final 'gateway' into the Highlands, as King Edward I found out. There was a primary need to be able to cross it and, at various points, there were well-known fords and ferries. But Boat O'Brig was unique in that a wooden bridge was built here very early on - perhaps in the days of King William the Lion. It was maintained by the Bishop and Chapter of Elgin in return for the tolls collected from every traveller. This was an exceptional contribution from the clerics to the people of Moray and one that would have been much appreciated in spite of the tolls. In medieval Scotland, a bridge was not a common feature to find anywhere and the fact that this one is known to have existed for hundreds of years is a great testimony to the dedication of the church authorities. However, as with many things, the Second Reformation swept the ecclesiastical structures away and with them went the bridge. The necessary maintenance and repair that the bridge would have required, and which was part of the 'contract' held by the Chapter, was completely neglected after the reforms of 1560, a time which ushered in a period of money-grabbing rather than the provision of any sort of service to the community! As would be expected, the bridge ultimately collapsed before the pressure of floodwaters. It was replaced with a ferry, and this gave its name to the location, but it would have been a meagre replacement for a bridge!

Ultimately, a replacement bridge was built which, in its own right, had a significant history, but this did not happen until 1830.2 It took the form of a suspension bridge and it is said to have been built according to the design of one Captain Samuel Brown. Captain Brown, a naval officer, received a knighthood in return for the important invention which he brought to the Royal Navy. He patented a system of manufacturing wrought iron chain cables which were employed to replace hempen cables for the standing rigging of ships and also in the manufacture of mooring cables. This same system was used in the construction of suspension bridges, such as that at Boat O'Brig and another, of his design, at Berwick-upon-Tweed, which gained him international renown.3 Unfortunately, it was the construction work required for this bridge that removed the last traces of the medieval hospital. It is said that, "the buildings survived the Reformation to a considerable extent, but were mostly removed for the rebuilding of the bridge in 1830, but what was supposed to be the east gable existed in 1870 as an old crumbling wall 3ft to 4ft high and 33ft long, forming part of the road fence."4 It was also recorded that there had been a graveyard discovered here. Captain Brown's suspension bridge across the Spey was itself replaced, in 1956 - by a girder bridge more suited to cars - and this carries the traffic to this day.

For many decades, then, the Bridge of Spey became a main east-west thoroughfare attracting travellers of all kinds. In time, and for reasons considered later in this article, a hospital was set up at the eastern end of the bridge to provide hospitality to those travellers who were in need of it. The whole establishment, which included a chapel, was dedicated to St Nicholas, the patron saint of seamen (more generally those who travel on water) and merchants.

John Grant suggests that, "This hospital [St Nicholas'] was founded before the reign of King Alexander II (1214-1249), and the situation was well chosen, as at that period there was a bridge over the Spey at that place."5 What he is saying here reinforces the fact that it was the bridge that was responsible for the desirability of having a hospital at the same location - they were to have a symbiotic relationship. It might even be argued that the hospital served as the toll-collector for the Bishop since it would make the whole matter of administration very much more simple. The tolls were destined for the support of the hospital anyway so why not have them collected on-site? But what is most important here is that Grant is saying, very clearly, that according to what he had learned, the bridge was present before the hospital was built.

There is a singularly good collection of charter evidence available to the modern scholar which shines a great deal of light on to the matter of the hospital's history.6 However, the collection should also cause students to question, again, certain issues that may have been glossed over by historians in the past. We should certainly question the following:

- Who built the bridge?

- Why was this location chosen for the bridge in the first place?

- Who built/founded the hospital?

- Did the hospital serve any other function?

The Bridge's Builder.

A charter of King Alexander II, dated securely to 30 June 1228, records the king's gift of his land of Robenfeld for the "sustenation" of the Bridge of Spey. In the charter, the King commands that the keeper of the bridge, [who is] to be appointed by the king and his council, shall have custody of the land thus granted and shall provide for the bridge's upkeep, as best as he can, out of the revenue derived from it.7 From this we gather that the king accepted significant responsibility for the bridge to the extent that the keeper was a King's Officer. We can also infer that the bridge was already in existence since the king is talking about its upkeep not its construction.

This is as close as we can get, using the written sources, to identifying the original builder, but it is worth pondering, 'who would want to, or who could afford to, or who would benefit most, by constructing a bridge?' My own belief is that it was either the king, or perhaps the king in collaboration with the bishop, since this solution would seem to answer best the questions posed.

Another significant fact is that, on a number of occasions, it is recounted that the bridge and hospital 'belonged' to the bishop. There is a strong suggestion here that they were 'his' because he (or a successor) had built them. Bridge-building was an accepted duty of a bishop in medieval times - very few lay people had the resources to fund such a project. The bishop had access to supplies of wood from his estates higher up the Spey; he had command of a work-force ready at hand and skilled craftsmen who would be capable of building the piers for a bridge; and, not least, he had the money! Either Bishop Brice (1203-1222) or his successor, Bishop Andrew de Moravia (1222-1242), would have been capable of initiating such a venture. Both men had significant plans for the improvement of their diocese and a bridge across the Spey would have strongly supported the ambitions of both men.

However, before we leave this matter, it is worth recording a local tradition which says that the first bridge at this location is supposed to have been built by the Romans under Severus.8

Location.

In considering medieval transport routes, is all too easy to allow our thoughts to be influenced by the courses taken by modern-day roads - the major one, the A 96, crosses the River Spey downriver from Boat o' Brig, at Fochabers. Of course, there was also a very old crossing point some 1.5km further to the north, opposite the church of Bellie, and this is the route that King Edward I took after passing through the lands of Enzie in 1296. The records are unclear whether this was a fording point or if there was a ferry but, considering the considerable numbers that are suggested for his forces, it is very possible that he employed both.9 A ferry boat crossing is also recorded very close to where the modern Fochabers bridges now stand. It was known as the Boat o' Bog, taking its name from the old name of the estate on the east side of the river - Bog o' Gight (now Gordon Castle).10 However, the route from this point westwards, to Elgin, was beset with navigating huge expanses of marsh, such as those of Dunkinty and Barmuckity, and many travellers preferred to take the more reliable route from Elgin along the old road through Rothes Glen. A quick glance at any map reveals that this glen takes one directly to the banks of the Spey at a point only a little distant from the Bridge of Spey. There was also another alternative - coming out of Elgin, via Linkwood, and then passing through Blackhills, Teindland and Inchberry to arrive at the Bridge of Spey - and this would have been the quickest option of all. The road from the bridge then runs true as an arrow towards Keith and the vast estates of Strathisla, with only a short piece of difficult terrain as one climbs from the bridge, up the side of the River Orkel (now known as the Burn of Mulben). A measure shows that this route is somewhat shorter than that via the Boat o' Bog and it also removes the need to pass over the Slorach which presented a significant climb of nearly 600ft - a major endeavour for heavily-burdened animals. The Boat o' Brig route does, however, present its own challenge since, although it is some 200ft less of a climb, it is steeper than the approach to the Slorach, but for those on foot or leading single horses, this would not have been a problem.

If the case is not yet made then one should consider that the Spey conveniently narrows at this point and it would have presented less of an undertaking to bridge it here that elsewhere. An inspection of the riverbanks reveals outcrops of rock on both sides, ideal for creating sound foundations for the bridge-ends. However, the main advantage was that this was exactly where the road appeared out of Glen Orkel onto the banks of the Spey.

We should also note here that in ‘modern’ times, when the railway was extended from Nairn to Keith via Elgin, the route chosen followed the old road beside the River Orkel and required the construction of a second bridge at Boat o’Brig. Permission for this route was given in July 1856 and the line reached Keith on 18 August 1858. However, the River Spey’s newest bridge was not yet complete and, for a period, the trains stopped at either end. The passengers had to disembark and walk across the road bridge whilst the carriages were uncoupled from the locomotive and hauled across the incomplete bridge by ropes. Once across, they were coupled to another waiting locomotive and the passengers embarked again to complete their journey. What is relevant here is that the route that was considered the best option in the early medieval period was still the most attractive to the engineers many hundreds of years later.

Founder of the Hospital.

Many writers have assumed that the Hospital was founded by Muriel de Pollok (Polloc), lady of Rothes,11 and there are, indeed, copies of charters preserved within the chartulary of the diocese of Moray that indicate that she was a great benefactor. One of these charters can be accurately dated to 6 December, 1238, and the wording indicates that the hospital

At about the same time that Muriel made her benefactions, Walter de Murref [de Moravia] granted to the hospital his lands of Agynway [Aikenway]

However, the above charters can both be ruled out from being acts of 'foundation' since the hospital was already in existence before they were enacted - they were both acts of 'endowment' not of foundation.

We then have a charter of Alexander II, King of Scots, granting to the chapel of St Nicholas by the bridge of Spey, 4 marks yearly out of the ferme of his mills at Invernairn in order to maintain a chaplain and a clerk. He instructs that half of the payment should be made at Pentecost and half at Martinmas. The date of the charter is exact - 7 October, 1232, given at Inuerculan (Cullen).14 Now a number of scholars have determined that since it was the chapel that was being endowed here, with no mention of a bridge, then this is proof that the bridge did not exist at this time. But I consider this to be incorrect - why would there be a chapel at this point on the Spey, one of sufficient importance that the king knew of it (and had probably visited it), if there was not a bridge (and possibly a hospital)? The situation is analogous to the hospital at Kincardine O'Neil on the River Dee in Aberdeen diocese. Here, the hospital was built after the wooden bridge, that was the first constructed across that river. What is certainly made clear is that the chapel (and hospital?) were in existence by 1232, which adds more evidence to support the fact that Muriel de Pollok's donation was an endowment,

In 1235,15 the hospital was further enriched by having the parish church of Rothes annexed to it. It is not clear from the chartulary who had been the instigator of this act, but it seems reasonable to assume that it was the church's patron, who at that time was the Lady of Rothes, Muriel de Pollok. This, again, was an act of endowment

The king's charter mentioned above is open to an alternative interpretation - the chaplain and clerk were destined for the "chapel of St Nicholas" but were they to be part of the staff of a hospital, or was there a period when there was only a chapel? Indeed, was there a hospital there at this date? However, the hospital certainly did exist by (1235 x 1242) since we find another charter confirming the gift of the church of Rothes "to the Hospital of St Nicholas, near the Bridge of Spey."16

The chapel and hospital were natural developments. Because of the superstitious nature of the populace, it was a noted feature in the north-east of Scotland that at any point where there was a significant crossing-point on a river, a chapel would often be built on one or other bank so that travellers could give thanks, either after a safe crossing or, in supplication for a safe crossing. The superstitious beliefs of the people of these early times (most of whom could not swim) was to consider that rivers were the residence of water-kelpies, demons, sprites, and all manner of devilish beings! Water, whether stagnant or flowing, was a source of immediate and mortal danger both to the body and the soul and any spiritual assistance was to be much sought after!

In conclusion, regarding the identity of the founder of the hospital we must accept that there is no definitive evidence, but, on the basis of the circumstantial evidence, I would favour placing the founder's mantle upon the shoulders of one of the bishops - perhaps Andrew de Moravia himself - with the assistance and encouragement of the king and such local magnates as wished to be associated with such a high-profile endeavour?

Ulterior motives.

It would be interesting to be able to see into the life of the hospital - how it was organised, how many staff it had and of what kind, was it purely for passing travellers or were there permanent residents, etc. Unfortunately, there is little or nothing left for us to find, although there is a charter of c.1391 which records the names of certain indwellers and which points to some of the residents, at least, as being permanently resident (vide infra). We also know that travellers only used the bridge after they had paid a toll and it would be reasonable to assume, therefore, that there were several staff to collect the money and guard the bridge from those who might otherwise try to cross without paying. There would also have been a need for staff to carry out domestic duties such as cooking and cleaning, keeping the farmland and running the mill, and, at the other end of the scale a number of priests and clerks who carried out their duties in the chapel as well as in the hospital. We know from the records that the house was ruled by a master but there is never any suggestion that the community existed together under any 'rule'.

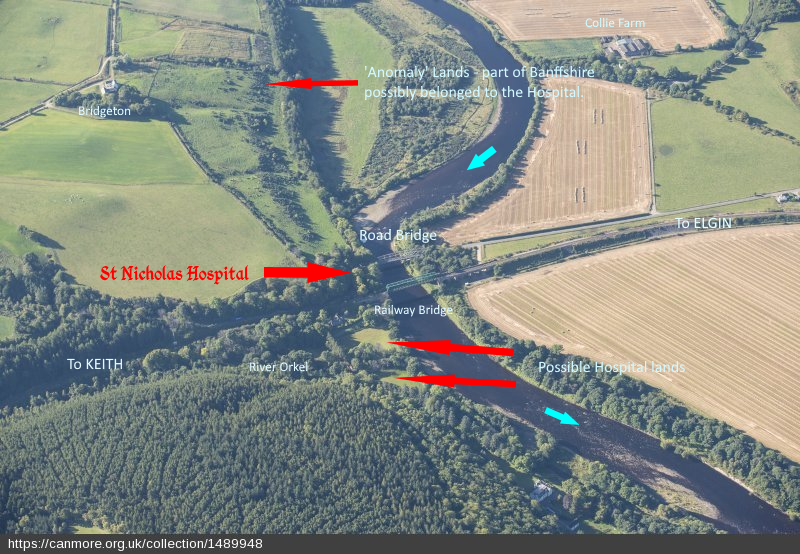

We know from the charter evidence that there was a mill at or near the hospital and there would, of necessity, have been many other buildings on the site. It is quite possible that the lands which were enjoyed by the establishment included some very attractive arable land on either side of the River Orkel where it enters the River Spey, and most would consider it unlikely that this land would not have been put to good use. There would have been a need for pasture for traveller's animals and sufficient arable land nearby to provide fodder for the animals, particularly in winter. It is possible that the land lying directly to the south of the hospital belonged to it also. About 0.5km along the road which runs through these lands is what is now a farm known by the name of Bridgeton which points to a settlement associated in some way with the Bridge

© HES Canmore Database with additions by David de Moravia.

They formed an 'enclave' of Banff-shire - an anomaly in the County boundaries.

Based on James Robertson's Topographical and Military Map.

© NLS Maps, Edinburgh.18

It is a matter of pure (but acceptable) conjecture to propose that the Keeper of the Bridge, and the other Hospital staff, provided another service to the bishop - that of running a medieval 'border crossing' that would have been of immense importance to the local administration. I have not encountered a similar suggestion in other sources but it would be very surprising indeed if we were to find that the bishop did not make use of such a facility to add to the information-gathering processes that would keep him, and the sheriffs, informed regarding who was passing into or out of the Province. Although the diocese extended much further east, the River Spey marked the traditional boundary of the ancient territories of Moray. The information that could be gathered at such a busy crossing point would have been of significant use to the authorities.

Should you wish to read a companion article about the Hospital of St. Nicholas at Boharm, written by Rev. Stephen Ree, a local minister, please press the button below. (This reference is in cluded in the 'Bibliography' below.)

In a charter dated to c.1391, contained within the Registrum Moraviensis, we have a record of what appears to be the whole of the hospital's community at that time.19

Bishop John Pylmore made Rogero de Wedale the first master {of the Maison Dieu} and Johanni Pylmor, monk of Cupar and the bishop's uncle, the second master, Simon de Carayl {Crail} the third, master Johanni Kynarde the fourth (he was of the bishop's kin); Bishop Alexander appointed Ade de Dundurkus and he remains master.

Witness: the Succentor of Moray {unnamed} signs and seals the attestation in the absence of the appropriate seal." {This was possibly John de Ard, succentor of Moray (1375-1394)}

| Date | x Date | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 30 June 1228 * | Moray Reg., no. 109; RRS, iii, 140 | |

| King Alexander II gifts his lands of Robenfeld for the sustenation of the Bridge. He reserves the right to appoint the keeper of the bridge. | ||

| March 1227 | 1230 | Moray Reg., no. 106 |

| Muriel de Pollok gifts all of her lands of Inuerorkel to the Hospital for the support of poor travellers. | ||

| 7 Oct 1232 * | Moray Reg., no. 110; RRS, iii, 181 | |

| King Alexander II gifts 4 marks p.a. from the ferme of his mill at Invernairn to maintain a chaplain and a clerk at the Chapel of St Nicholas. | ||

| 1235 * | Moray Reg., 111; St A. Lib., 326-7 | |

| Bp. Andrew, Prior of St Andrews, Muriel de Pollok (as patron), all agree to the church of Rothes being annexed to the hospital. (It had previously been annexed to the priory.) The priory was to receive 3 marks yearly in recompense. | ||

| 1235 | 1242 | Moray Reg., no. 113 |

| Bp. Andrew confirms the hospital's possession of the church of Rothes. | ||

| 7 Oct 1224 | 17 Dec 1242 | Moray Reg., no. 108 |

| Walter de Moravia gifts his lands of Agynway, one dabhach, but not the fishing, to the hospital for the paupers there (at St Nichols' Hospital). | ||

| 6 Dec 1238 * | Moray Reg., no. 107 | |

| Muriel de Pollok gifts to the hospital her mill at Inuerorkel and lands to the east between Orkel and Spey for poor travellers. | ||

| 6 Dec 1238 | 1242 | Moray Reg., no. 112 |

| Eva Morthach (Murdoch)17, Muriel de Pollok's daughter, confirms all of her mother's gifts to the hospital. | ||

| c.1391 | Moray Reg., no. 117 | |

| Attestation of certain 'indwellers' of the hospital regarding the Maison Dieu in Elgin. | ||

| * signifies that the exact date of this charter has been determined. | ||

1. Shaw, L. (1775) The History of the Province of Moray, Vol. 1, New Edition, J.F.S. Gordon, ed. (1882), Glasgow: University Press, p. 65. Return

2. In 1820, Brown completed a suspension bridge (the aptly named Union Bridge) across the border over the River Tweed, between Horncliffe, Northumberland and Fishwick, Berwickshire. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Union_Bridge_(Tweed) (accessed 03/06/20) Return

3. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trinity_Chain_Pier (accessed 03/06/20) Return

4. Easson, D.E. (1957) Medieval religious houses in Scotland: with an appendix on the houses in the Isle of Man, London, 155. Return

5. Grant, John (1798) A Survey of the Province of Moray: historical, geographical, and political, Aberdeen: for Isaac Forsyth, Elgin, Booksellers, p. 80. [Available as an e-book from Google Books.] Return

6. (See table above.) Return

7. Moray Reg., no. 109, dated 30 June 1228, at Elgin; RRS, iii, no. 140. Return

8. Lewis, Samuel (1847) A Topographical Dictionary of Scotland, London, q.v. "Boharm". Return

9. For details of King Edward I's 'progress' see, Gough, H. (1900) Itinerary of K. Edward I Throughout His Reign. 2 vols. Paisley: Alexander Gardner, and Taylor, James (1885) Edward I in the North of Scotland. Elgin: James. Return

10. There was also a ferry-boat at Spey Bay but such have been the movements of the shingle banks that even the exact location of the mouth of the river is difficult to determine through the ages, let alone where the ferry ran! Return

11. For example Richard Fawcett in Fawcett, R. and Oram, R. (2001) Elgin Cathedral and the Diocese of Moray, Historic Scotland, p. 129. Return

12. Moray Reg., no. 107, dated St Nicholas' Day (6 December), 1238. Return

13. ibid., no. 108. Return

14. ibid., no. 110, dated 7 October 1232, at Inuerculan; RRS, iii, no. 181. Return

15. ibid., no, 111; St A. Lib., 326-7. The year here is exact since it is given in both charters. The parish church of Rothes had been annexed to St Andrews Cathedral Priory at an earlier date and here we have the three parties involved in its transference to the Hospital of St Nicholas - the bishop of Moray [Andrew de Moravia] as diocesan and ordinary; the prior of St Andrew's, H[enry de Norham] who was losing the benefice; Muriel de Pollok, as Lady of Rothes, who held the patronage. The St Andrew's Lib. entry records that what was being done had been approved by W[illiam Malvoisin], bishop of St Andrews, and that the priory was to receive 40s p.a. from the 'rector' of the hospital - 20s at Martinmas and 20s at Pentecost - in recompense. The signatures appended to the two charters show clearly that the one in the Moray Registrum was a copy signed by the community of the Priory, whilst that included in the St Andrews Liber. is a copy signed by the Chapter of Moray. Return

16. ibid., no. 113, dated 4 September 1230 x 26 July 1232. Return

17. Scholars usually give Eva's surname in a modern form - 'Murdoch'. However, in the charters, its original form was 'Morthach' [Moray Reg., No. 112]. Might we at least consider that we should not read it as Murdoch (which is a 'strained' translation) but rather as 'Mortlach' (where the 'l' might have been mistaken for an 'h')? Mortlach is very close to Rothes and it would not appear impossible that Eva used this name as the result of her inheriting certain lands in Mortlach which were part of the Rothes barony. Return

18. Robertson, James (1822) Topographical and Military Map of the Counties of Aberdeen, Banff and Kincardine, (1 map on 6 sheets), London, sheet 2. https://maps.nls.uk/view/74400182 (accessed 21/06/2020) NOTE: This map shows the old course of the Spey before a great westwards meander was created (see aerial photo for comparison). Return

19. Moray Reg., no. 117. Cosmo Innes, who edited the Registrum, dated this 'attestation' to c.1391. Return

Ree, S. (1901) 'The Hospital of S. Nicholas Beside the Bridge of Spey.' Transactions of the Aberdeen Ecclesiological Society, Vol. 16. (1901), pp. 34-39.

e-mail: admin@cushnieent.com

© 2020 Cushnie Enterprises

(Edited 14/02/2025)