The Tironensian House of Ardlogy

at Fyvie

Over the years, an extensive collection of prehistoric remains has been found in the locality of Fyvie, ranging from stone axes, to spindle whorls, carved stone balls, a stone mace and many flint arrowheads. Consequently, there can be little doubt that this was an important center of population from the very earliest times. The reasons why this came about are not difficult to discern. Writing the entry for Fyvie parish in the Old Statistical Account, the minister, the Rev Mr. William Moir, commented as follows:

“The soil is various, but in general kindly, and yields pretty good early crops of bear and oats, especially in the neighbourhood of the church and Fyvie Castle. The more remote parts, particularly near the mosses and moors, are of a colder nature and [crop] later.”1

Since ancient times, then, Fyvie has been a pleasant and, more importantly, a very productive place to live. If you add to the Rev Moir’s comments the additional facts that the lands which became the parish of Fyvie had huge deposits of peat which could be exploited, extensive ‘forests’ for hunting and a plentiful supply of good water – either from the River Ythan or the many excellent springs that litter the area - then you can not be surprised that this locality has proved to be so attractive to humans ever since pre-historic times.

The Parish lands and Church.

Dark Age evidence is not lacking either although it is not to be found in such abundance. From Fyvie itself and ‘the environs’, we have a collection of Pictish Stones of the 7th Century. Although only one of them is thought to have been found in the graveyard of Fyvie Parish Church,2 the other two were found only a short distance away – one set into a wall of what had once been the village school of Fyvie3 and the other which, for a time, lay at Rothiebrisbane House, having previously been found acting as a drain-cover on the Rayne to Auchterless road at Tocherford

© Historic Environment Scotland

Perhaps the most important of the four stones is one which is currently considered to be a fragment of a Class III free-standing cross of the 9-10th Centuries.5 Although now reasonably secure and set into the surface of the east-wall of the parish church, in the early 19th Century it was handled somewhat less carefully – found by the minister (in the graveyard, it is believed) he had it ‘trimmed’ in order that he could use it as a door-lintel of the church building that was erected in 1803. As we have noted, archaeologists consider that, rather than being part of a cross-slab, it may represent a fragment of a much more high-status free-standing cross. Carved from red granite,6 it’s composition comprises ‘key-pattern’ and ‘triangular interlace’ carving and it must represent the product of considerable amounts of skill and time. Most importantly, of course, the presence of such a stone allows us to speculate that Christianity arrived in this area at a very early date indeed and that there may have been a muinntir here of some importance.7 However, there is no certain evidence to say that this stone is ’local’ to Fyvie, and other fragments have yet to be found. Granite is not the local Fyvie stone - that being sandstone of a deep red to purplish-brown colour. The nearest granite outcrops occur at Peterhead and Strichen. The Strichen stone is of a grey colour but that from Peterhead is described as being 'pink'.

In the early medieval period, the lands of Fyvie formed a royal hunting-forest and it is thought that there was a rude ‘hunting-lodge’ somewhere in the region of where Fyvie Castle now stands. The name ‘Fyvie’ is thought to mean deer hill8 which, if true, would echo the hunting theme. These lands remained the property of successive Scottish monarchs up to the 14th Century when they were assigned out of Crown ownership.9 Fyvie Castle, or a predecessor at or near the same site, was the chief messuage of the Thanage of Fermartyn.10

A parish church must have existed at Fyvie from before the time of William the Lion (1189-1199), indeed, Manson suggested that it was established by Fergus, Earl of Buchan, in 1179.11 It might be closer to the truth to suggest that there had been a church at Fyvie for many years before this and probably from long before the time when parishes first appeared in Scotland. With the dawn of Anglo-Norman church structures and organisation, it is most probable that one of the significant land-owners determined that the church of Fyvie should follow the trend and become a parish church. This may have been Fergus, Earl of Buchan c.1179, but it could just as possibly have been a predecessor such as Gartnait (d.1132x1135) or Colban, both mormaers of Buchan in their time. My own opinion is that since the major local land-owner was the king, then it would be logical to presume that he would have been the prime mover in making a church, that would have been well-known to him, and which served the royal demesne, a parish church.

The church lands of Fyvie, along with the parish church, were granted to Arbroath Abbey by William the Lion (1189x1194)12 and confirmed to the uses of the abbey by Matthew, bishop of Aberdeen (1179-1199).13 A vicarage perpetual had been erected by 1257, whilst the abbey enjoyed both the rectory and the vicarage tithes.14 This arrangement was confirmed by Pope Alexander IV.

King William I. was present at Fyvie on 9th October, 1211x1213 (probably 1211), on which date he issued a charter in favour of Dunfermline Abbey.15 The witnesses to the charter comprised a group of senior nobles which has the appearance of being a party attending the king as he travelled round his territories. It would appear that they were using the lodge at Fyvie as a place for some rest and recuperation, where they could all also enjoy the thrills of the chase! One week before this, the king had been in Forres where he had given a charter to William Cumin and his heirs.16 On October 15th, six days after the king signed the charter at Fyvie, he was in Forfar where he confirmed a grant made by Hugh Malherbe to Arbroath Abbey.17 This is a good example of the 'mobility' of the king and his close advisors in these times.

On 22nd February, 1221-2, King Alexander II granted a charter confirming the church of Bethelnay (Old Meldrum) to the monks of St Thomas at Arbroath. The charter is dated "apud Fyuyn" (at Fyvie).

In 1286, the Thanage of Fermartyn was held by Reginald le Chen (‘pater’) (†1293) but there has never been much clarity amongst historians as to how he obtained it. However, an examination of the Exchequer Rolls reveals that Reginald was, in fact, Firmarius de Fermartyn, i.e. he held the Thanage not hereditarily, but on lease from the king.18 In their time, this family formed a very powerful dynasty who held vast estates in various parts of the country and were Sheriffs of Kincairdin (Kincardine).19 Sir Reginald (pater) was also Lord High Chamberlain of Scotland from 1267-1269, making him the third Great Officer of State.20 Successive members of this family held important positions both at court and in government, and carried out embassies of the highest order on behalf of their king and country. They held great power and influence and served their country exceptionally well and their vast wealth and position allowed them to be great patrons, as we shall see. It is to be regretted that they are not better-remembered since they deserve a place alongside the famous families of Gordon, Innes, Forbes, etc., and other great families from the north of Scotland. However, the male-line of the family of le Chen (Cheyne) died out a very long time ago and this has inevitably resulted in them fading into the background of Scottish history.

Reginald I le Chen’s son, Sir Reginald II le Chen (c.1235-1312), married Mary,21 daughter of Freskin II de Moravia, and through her, he obtained the lordship of Duffus in Moray, which included the famous castle.22 He was also appointed constable of the royal castle at Elgin. Consequently, Reginald became the holder of a substantial ‘estate’ – one of the largest in the country – since he had also inherited through his wife the southern estate of ‘Strabrock’ (Strathbrock) and the lordship of Strathnaver in the north of the country.

To the north-east of Fyvie and wrapping round to the south of the old royal forest, lie the lands of the barony of Lethendy including that part known as Ardlogy. As has been said, at some date the ‘le Chen’ (Cheyne) family became firmarii [feuars] of the whole of Fermartyn (Formartine) including the barony of Lethendy.

As late as 1325, the situation regarding land-ownership in the vicinity of Fyvie was still not clear and King Robert Bruce, possibly in exasperation, issued a brieve to fix the marches between the King’s park of “Fyvin,” and the lands of Ardlogie, belonging to the Abbey of Arbroath.22b The matter was not helped by the fact that the ‘barony of Fyvie’ was also known in the charters as ‘the barony of Fermartyn (Formartine)’ - the ancient barony of Formartyn formed three-quarters of this district, the other one-quarter constituting the barony of Belhelvie.

In the late 14thcentury, the whole nature of land-ownership and land-tenure began to change and a measure of confusion ensues because the records regarding Fyvie were no longer kept by the Crown, but rather by the families who became the 'proprietors' of the estate. It is a matter of note that a significant collection of charters was maintained within the security of Fyvie Castle and so it is not as badly served in the historical record as some estates.

"In the year 1616, Alexander, Earl of Dunfermline, the then proprietor of Fyvie Castle, had a charter from King James VI., uniting the rectory and vicarage of Fyvie into one benefice, and conferring on him the advocation, donation, and right of patronage of the parish church; since which time the patronage of the benefice has gone with the Castle property."22c

The Priory of Ardlogy

The Priory that was situated on the lands of Ardlogy, near Fyvie, is well-known – it being a daughter house of the Tironensian Abbey of Arbroath, which had been founded by King William the Lion in 1178. The house at Ardlogy was founded some years later and was dedicated to St Mary and All Saints. The name of the priory is often given as Fyvie Priory by modern writers, but research shows that in the early charters it was called the Priory of Ardlogy and, since it was located in the upper reaches of the lands of Ardlogy, in the thanage of Fermartyn, rather than within the royal estate of Fyvie, we choose to use its older name here and would urge others to do the same.

On the Feast of St Luke, (18th October), 1285, Reginald II le Chen (Cheyne) (1235-1312) gave the lands of Ardlogie and Leuchendy (Lethindy), and certain others, to Arbroath Abbey – “to the monks of that monastery perpetually serving and thirsting for God in the religious house built at Ardlogie, near the parish church of St Peter at Fyvie.”23 The details of the grant are very important to our case since the wording and sentence structure leave little doubt that the priory was already in existence at the time of Reginald’s gift. Although the gift was intended for the benefit of the daughter-house of Ardlogy, it needed to be made to the mother-house at Arbroath which would then be responsible for seeing that the benefits were used to the advantage of the priory. It is important to stress here that this gift of Reginald II le Chen was to augment the priory's income. Reginald's gift was intended to provide it with sufficient lands, adjacent to whatever buildings had been constructed, to support the community and to subsidise further building. The lands of Ardlogy lay immediately to the south-east of the priory whilst those of Lethindy (Lethenty) lay some 5km north-east of it, at

The same day that Reginald II made his gift, and most likely at the same time that he signed his charter in Aberdeen, recording the donation, (Thursday, 18th October), Henry le Chen, bishop of Aberdeen (1282-1328), who was probably the brother of Reginald II le Chen, annexed the vicarage of the 'local' parish church of Fyvie to the house of Ardlogy, in proprios usus, the parish cure to be served thenceforward by a chaplain, “qui parochiam die noctuque cum necesse fuerit circumeat ac parochianis sacramenta ecclesiastica ministret.” 24 In his charter the bishop says quite explicitly that the house had been founded by Reginald le Chen (pater), i.e. Reginald I le Chen - "… quam nobilis vir Reginaldus le Chen pater fundavit …".24b Most importantly, the bishop's charter tells us clearly that the Priory of Ardlogy, having been founded by Reginald I le Chen (the father), was now being further endowed by the founder's son, Reginald II le Chen. These arrangements resulted in a lengthy series of disputes between successive bishops of Aberdeen and abbots of Arbroath and, in an attempt to reach a settlement, it required the vicarage to be re-annexed to Ardlogy priory in 1399.

On 4th January, 1425, Walter Paniter, abbot of Arbroath (1410-1449)26 obliged the Abbey for the annates27 of the church and perpetual vicarage of Fyvie. It might be suspected from this that, before this time, the Abbey had not seen the payment of annates as being its financial responsibility, but may have, rather, expected the parish to be responsible for paying the annates (in addition to the monies that they were required to pay to the Abbey).

On 20th June, 1427, soon after his return from Rome, Bishop Henry de Lichton, at the desire of the abbot and convent of Arbroath, confirmed to their cell at Ardlogy, the vicarage of their church of Fyvie, it being vacant because of the resignation of the previous vicar, Johannis de Crabe. The bishop imposed a condition that the brethren of Arbroath should give the vicar ten marks yearly and a sufficient manse. They were also bound to make payment yearly of six marks to a chaplain serving in St Machar's Cathedral in Aberdeen, and to find him a decent habit to wear.27b

The evidence here points to an on-going dispute between the bishop and Arbroath Abbey and, as a consequence, Bishop Henry was being required to annex the vicarage of the parish church to the priory again. This time, in so doing, the bishop stipulated that 'the cure' should be served by a vicar pensionary and also that payment should be made from the fruits of the church of Fyvie (controlled by Arbroath Abbey) to support a chaplain in his cathedral at Aberdeen. The first effect of this was that the parish of Fyvie would, in future, be served by a vicar rather than by a chaplain and that the vicar would enjoy a regular ‘pension’ (stipend) to be paid by Arbroath Abbey.25 The parishioners might also have been much happier with this arrangement since it would then be more difficult (if not impossible) for 'the cure' to be served by one of the priory's community - seldom a happy arrangement for a parish. The second effect was that the bishop's edict enabled him to re-affirm his authority as 'ordinary' over the incumbent of the parish church - a monk would always have been more likely to see his abbot as his source of authority which could lead to serious difficulties, if not conflicts. Also, in the previous arrangement, the parishioners could never be sure which of the monastic community was their priest. Thirdly, the new arrangement meant that the parish would be likely to have a more experienced, and possibly more learned, priest who would be better able to serve the cure since it would be the only focus for his attentions. Fourthly, the new arrangement also meant that the Bishop was able to assign funds - to be paid by the Abbey - for the establishment and maintenance of a new chaplain to serve in his cathedral church at Aberdeen. In effect, this would have prevented such a large proportion of the ‘fruits’ of the parish church of Fyvie from disappearing out of the Diocese and into the Abbey’s coffers. It is no surprise that the move should have resulted in a dispute!

These arrangements continued until moves were made to re-unite Ardlogy Priory with Arbroath Abbey c.1508, when both the parsonage and the vicarage revenues of Fyvie parish church accrued to the Abbey. However, up to c.1540, the priory seems still to have been recognised as a separate entity since a succesion of commendator priors were appointed. But these individuals would appear to have been priors in name only, the community having left the buildings at Ardlogy and returned to Arbroath.

The Priory Buildings

According to the Rev John Manson, the priory lay, “on a meadow between the Parish Church and the Bridge of Lewes.”28 Another Fyvie minister, the Rev William Moir, who wrote the entry for Fyvie in the Old Statistical Account, had this to say:

“Near the church, on the banks of the Ithan (sic), are the ruins of a priory, said to be founded by Fergus Earl of Buchan, in the year 1179, and his donation of it to the Abbacy of Arbroath was afterwards confirmed by Margaret, Countess of Buchan, his daughter, who married Sir William Cumming, Knt., who, by that marriage, became Earl of Buchan. From the appearance of the foundations, which were extant some years ago, it should seem to have been 3 sides of a court, the middle of which was the church, and the 2 sides the cells and offices of the monks. It does not seem to have been richly endowed, for the lands that belonged to it in this neighbourhood, amount only to L. 200 Sterl., of rent at this day.”29

If we presume that the priory's church lay on a traditional East-West orientation then the two ‘wings’ probably ran southwards. This would have created a south-facing enclosed area for a garden to supply a portion of the needs of the priory. Since the priory buildings lay undeveloped on one side of the 'rectangle', it would seem to imply that there was no cloister as such, although there may have been a covered walkway, lightly constructed of wood, that acted as a cloister.

The rule of the Tironensian Order was basically that of St Benedict but the houses of Tiron placed a greater emphasis on poverty and hard physical work. In particular they stressed the encouragement of artisan skills - working with wood, metal, and stone, and in great endeavours on the land. We have already noticed that Ardlogy was, comparatively speaking, prime agricultural land and, consequently, it is reasonable to assume that a great deal of the monks’ time would have been devoted to farming it. Of course, they would also have required the skills that would have allowed them to construct the priory buildings. It is known that in the Tironensian houses in England and Wales, monks from the founding house would bring their skills to a daughter house to help in its construction and this might well have happened at Ardlogy since Arbroath Abbey must have had some seriously skilled builders amongst the ranks of its community.

There were a number of other Tironensian priories scattered across Britain, especially in Wales. Few of these were large establishments although some had extensive buildings at their disposal. It was not uncommon to find that the community in these priories numbered only three or four monks, and, at times, there was only one, so the priory resembled a hermitage rather than a community. Very few names have come down to us but a list of some of the priors who served at Ardlogy is contained in Apendix A., at the end of this article. It would not be unreasonable to imagine that what is regularly referred to as the House of Ardlogy functioned as a grange for these northern lands. In many ways, there are similarities between it and Dunfermline Abbey's Priory (Cell) at Urquhard, just east of Elgin. There would never seem to have been a large group of monks at Ardlogy, but there would have been a substantial group of lay-brothers employed on the land. As at Urquhard, Ardlogy might have offered an attractive opportunity to the monks serving the mother house for some rest and recuperation, especially in the summer months. It would also offer the abbot at Arbroath an opportunity to provide a monk with the opportunity to show himself worthy and able for further preferrment within the mother community - to sub-prior or prior.

One major remnant of the Priory 'establishment' is still to be found. Although now a modern building, it stands on the original site of the monks' mill, which was used to process the produce from their fields. This property is now called Mill of Ardlogie

© Scotland's Places.

The map from which the extract above has been taken is a superb piece of work and includes all of the lands of Woodhead, Fetterletter, Petts, Monkshill, Lethenty, Oldmoss, Moss-side, Gight, Stonehouse, Blackhillock and Little Gight.30

Only a short distance to the east of Fyvie lies the old settlement of Woodhead of Fetterletter which was once a burgh of barony. Here, there is the handsome Episcopal Church of All Saints

© Cushnie Enterprises.

© Cushnie Enterprises.

© Cushnie Enterprises.

© Cushnie Enterprises.

© Cushnie Enterprises.

Having made enquiries of Àrainneachd Eachdraidheil Alba (Historic Environment Scotland) and Professor Jane Geddes, there is now a suggestion that some of these stones at Woodhead are of late 15th - early 16th century provenance and not, therefore, associated with the earlier priory buildings at Ardlogy. A suggestion has been made that the three crosses and the 'IHS monogram stone' could have come from the debris that resulted from the the early 19th cetury restoration of Fyvie Castle.31b Professor Jane Geddes has also pointed to a 16th century date.31c Stephen Holmes has suggested that, " … the crosses and the arrows are later than Fyvie Priory and the IHS is associated with that group of Catholic houses in the area studied by Alasdair Roberts …" 31d

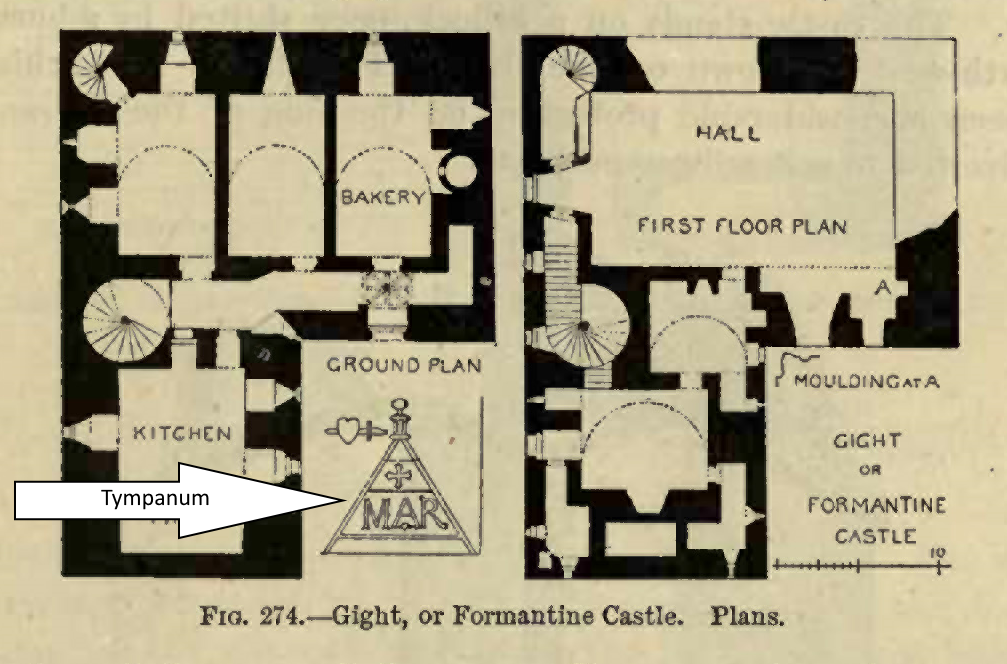

Recently, we came across a sketch in MacGibbon and Ross relating to the ruined remains of the Castle of Gight which lie only a little distance from Ardlogy.36 Added to the ground plan is a drawing of a tympanum of a dormer window which was still existent at the time the plan was made. The authors wrote, "From the thickness of the walls, and the number of wall chambers and other features, this castle evidently belongs to the fifteenth century, although probably it was remodelled at a later date. The remains of the tympanum of a dormer window still existing (see sketch) seem to point to this."

A georeferenced map is available showing the lands associated with the Priory … as originally mapped by John Hume in 1768. It is superimposed on a 'modern' map of the area. The georeferencing is not completely accurate but it does show the position of the Priory with reference to the village of Fyvie and also other 'sites' mentioned in the text.

PRESS HERE…to see

Georeferenced Map!

| Name | Dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Neso | 1312 | Prior |

| Albertinus | 1323-1325 | Custos |

| John Fewir (Senir) | 1362 | Custos |

| Patrick de Infirmiterio | 1362-1364 | Custos later Prior |

| John Gedy | 1371-1384 | Prior (later Abbot of Arbroath) |

| John Scot | 1395 | Prior |

| John de St Andrews | 1425-1450 | Custos later Prior |

| Malcolm Brydy | 1450-1455 | Prior (later Abbot of Arbroath) |

| Alexander Mason | 1459-1508 | Prior |

| James Hering | 1508- | Prior |

| Thomas Nudry | 1516 | Commendator |

| Thomas Currour | 1529-1531 | Commendator |

| David Betoun | 1531 | (Was in litigation with Currour 7 Jan 1531.) |

Source: Watt, D. and Shead, N. (2001) Heads of Religious Houses in Scotland from Twelfth to Sixteenth Centuries, Edinburgh: The Scottish Records Society.

(Watt & Shead state that, "This priory appears to have continued as a separate entity at least until the 1530s (when there was a dispute over the priorship in 1531) and 1540s (when it was assessed for taxation)."

In order to fully understand and appreciate the history of the Priory of Ardlogy it is necessary first to understand the events which took place more generally in Alba32 in the eleventh and twelfth centuries which determined the changes which took place to the structure of land-holding - mormaerships and thanages - and, in particular, how the Thange of Fermartyn was affected.

In the Preface to his work, the Rev William Temple quoted a twelfth-century source which stated, "Quartum regnum fuit ex Dee usque ad flumen Spe majorem et meliorem totius Scocie" (The fourth 'kingdom' was from the River Dee to the River Spey, the greater and better of all in Alba.)33 Temple himself described Fermartyn as being part of a confederacy which encompassed the districts known as Mar and Buchan, which confederacy was one of the seven that then comprised Alba. However, most historians have considered Formartine to be that portion of land lying between the Rivers Ythan and Don, with the North Sea marking the eastern boundary and the neighbouring Thanage of Conveth the western limit.

Since very early times the lands of Fermartyn have been retained as 'royal lands' and, indeed, we find the Park of Fyvie being called the "King's park" in 1325.34 The royal demesne at that time seems to have comprised the lands of Gourdas to the north-east of Fyvie at

References.

1. OSA, p.460. https://stataccscot.edina.ac.uk/static/statacc/dist/viewer/osa-vol9-Parish_record_for_Fyvie_in_the_county_of_Aberdeen_in_volume_9_of_account_1/osa-vol9-p459-parish-aberdeen-fyvie?search=Fyvie Return to Text

2. HES Canmore Database - Permalink: http://canmore.org.uk/site/19033 The stone is recorded as Fyvie 1. Return to Text

3. HES Canmore Database - Permalink: http://canmore.org.uk/site/19034 The stone is recorded as Fyvie 2. Return to Text

4. HES Canmore Database - Permalink: http://canmore.org.uk/site/19036 The stone is recorded as Fyvie 4. Return to Text

5. HES Canmore Database - Permalink: http://canmore.org.uk/site/19035 The stone is recorded as Fyvie 3. Return to Text

6. Although nothing can be certain, it may be that this stone originated from the area of Peterhead where ‘red granite’ is found in abundance. The granite outcrop further north at Strichen is mostly grey in colour. Return to Text

7. Simpson, W.D. (1935) The Celtic church in Scotland: a study of its penetration lines and art relationships, Aberdeen: University Press; Aberdeen University Studies, 58. Return to Text

8. It is said to derive from the Gaelic: fùbhaidh or fiodhbhadh both old words for “wood”. Return to Text

9. HES Statement of Interest (2011) Fyvie Castle GDL00184, Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland. http://portal.historicenvironment.scot/designation/GDL00184 Return to Text

10. Temple (1894), 18. Return to Text

11. Rev John Manson, in the New Statistical Account, quoted in Pratt (1858), p. 259. [NSA, Vol. XII, p.315]. Manson said that he was quoting Spottiswood. Return to Text

12. RRS., ii., 356, p.353. Witnesses were: Herbert de Camera; Philip de Valognes (chamberlain); Richard Revel, lord of Coultra; Richrd, son of Hugh de Camera; Robert of London, illegitimate son of the king; William Comyn, Earl of Buchan and Justiciar of Scotland; William del Bois (Boscho), Chancellor. Return to Text

13. SEA., i., no.2. In this charter, Matthew, bishop of Aberdeen, granted, a group of six parish churches from his diocese – Inverboyndie; Banff; Fyvie; Banchory-Ternan; Gamrie with the chapel of Troup; and Tarves with the chapel of Futhcul [Fuchill] - to Arbroth Abbey. Return to Text

14. The church and lands of Tarvays (Tarves) were given to Arbroath Abbey in like manner and at the same time. [SEA.,i., no.2] Return to Text

15. REA., ii., no. 502, p.455. Return to Text

16. REA., ii., no.501, p.454. Three of the witnesses are the same as those who witnessed the Fyvie charter. (William del Boscho, Philip de Valognes, Herbert de Camera.) Return to Text

17. RRS., ii., no.503, p.455-6. Only two of the witnesses are the same as those who witnessed the Fyvie charter. (William del Boscho, the chancellor, Robert de London. Return to Text

18. Echequer Rolls, i., p.21. “Computum eiusdem Reginaldi, firmarii de Fermartin, etc. De firma thanagii de Fermartin. Recepte, etc. Expense, etc. Item, per terram de Kilmclome datam burgensibus de Fyuyn de illo anno, x marce.” The term ‘Firmarius’ was used to refer to a person who held lands as a tenant. (Lat: firmārius m (genitive firmāriī or firmārī) = ‘tenant’) https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=fuam4DKs1RoC&printsec=frontcover&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false Return to Text

19. Exchequer Rolls, i., p.20. The Sheriff was the ‘King’s Officer’ in the part of the country so designated. Return to Text

20. Sir Reginald is often to be found in records referred to as ‘patris’ (father) to avoid confusion with his equally famous son who was also called Reginald. Return to Text

21. Mary de Moravia is sometimes also called Helen. Her mother was Joanna of Strathnaver, Lady of Strathnaver in her own right since she had inherited from her father. (See Crawford, B. (2019) ‘Medieval Strathnaver’, in The Province of Strathnaver, John R. Baldwin (ed)., Edinburgh: the Scottish Society for Northern Studies, pp. 1-12.) Return to Text

22. In 1305, it is recorded that, “on the petition of Sir Reginald le Chen for 200 oaks to build his manor of Dufhous,” the king’s response was, “The King wills it.” It is believed that the trees were to come from the royal forests of Longmorn and Darnaway. This represents an enormously generous gift from the King, who also, on the petition of John de Spaldyng, canon of Elgin [cathedral], gave another 20 oaks “to build Dufhous church.” [CDS., iv., 375] https://archive.org/details/cu31924091754410/page/374/mode/2up Return to Text

22b. RRS., v., no.280.; Permalink: www.poms.ac.uk/record/source/10003/ "Robert, king of Scots, to his beloved and faithful chamberlain Alexander Fraser knight or whomever his lieutenant or lieutenants may be, commanding a recognition (inquest), firmly observing the assize of the land, to be made by the worthy and faithful and older men of the country in order to determine the full truth of the bounds between the land of Ardlogie which belongs to Arbroath abbey in the sheriffdom of Aberdeen and the king's park of Fyvie, and if the burgesses of his burgh of Fyvie have or were wont to have in the time of King Alexander III any interests in the peatary [a place where peat is excavated] of Ardlogie or the adjacent park and whether these were by right or through the generosity of the said monks; saving the right of his burgesses to have the inquest made in his presence according to the said assize." Return to Text

22cNSA, no. xxviii., p. 328. Return to Text

23. REA., ii., xxvi.; Liber Arbroath, 234, p.166. (English trans. at Permalink: www.poms.ac.uk/record/source/4565/) Return to Text

24. "… to be available day and night, when necessary, to administer the sacraments to the parishioners.” [Liber Arbroath, 235, p.167] (English trans. at Permalink: www.poms.ac.uk/record/source/1356/) Return to Text

24b. Arb. Liber., i., no.235. Return to Text

25. A chaplain would have had to support himself on the various payments made by the parishioners for his services to them. Return to Text

26. Watt and Shead (2001), 6. Return to Text

27. Annates was a yearly payment to be made by a parish to the Diocesan Bishop in order that the diocese could pay the annates which it, in turn, was required to pay to the Holy See. Return to Text

27b. REA, i, p.224; McLeod (1899), 129-130. Return to Text

28. Pratt (1858), 259. Return to Text

29. OSA, Vol., IX., 1793, p.463. Return to Text

30. John Hume Map (1768). Plan Of The Lands Of Fyvie And Surrounding Lands, Aberdeenshire | Scotlands Places Return to Text

31. It is thought by some historians that Woodhead was a Royal Burgh at some point in its history. However, conclusive evidence is yet to be found. Return to Text

31b. (Personal email from HES Archives on 25/08/2022) "… when I first saw these stones I was not impressed by this [Ardlogy Priory] as their origin: the pediments for instance speak to me of the later 16th or early 17th century. The form of the cross would similarly be unusual in a pre-Reformation context in Scotland, as would the IHS monogram. Both are more characteristic of the later 16th century onwards. The arrow finial also, to me, has a post-Reformation feel."

31c. (Personal communication from Professor Geddes on 09/08/2022) " The lettering on the IHS pediment is 'humanist capitals' which become very fashionable in Scotland in the C16, when the cult of the 'Name of Jesus' was also popular." What is interesting about this survival is that at the Reformation IHS was deliberately defaced by the Presbyterians and only a few remain in Aberdeenshire. Presumably this one was too high up to smash. Another survives in a misericord at King's [College] Chapel, Aberdeen, hidden beneth the seat."

31d. (Email from Stephen Holmes to Jane Geddes, 11/08/2022); Bryce, I.B.D. and Roberts, A. 'Post-Reformation Catholic Houses of north-east Scotland,' in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, (1993) Vol. 123, p. 363-372. https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-352-1/dissemination/pdf/vol_123/123_363_372.pdf

32. The name Alba is used by historians to refer to the lands which lay towards the east of the country, and between the River Forth and the River Spey. This was the part of the country which was securely under royal control and influence whereas the remaining parts - Lothian, Lennox, the Western lands (including the Islands), Moray, Ross and Sutherland - were not. Return to Text

33. Temple (1894), vii. Return to Text

34. Lib. Arbroath, i., 311. Dated "Monday after the festival of St Bartholomew the Apostle, 1325" (26 August, 1325): This was a 'Recognitio' (review) of the divisions of Ardlogy and Fyvie. The Sherrif of Aberdeen (Johannes Drimmyng) taking the place of the Lord Chamberlain of Scotland (Alexandri Fraser), on the moor beside the park of Fyvie, having received a brieve from the King, walked the bounds along with a large number of notable men, including two abbots - of Kilwinning and Deer - and Walter Story the Official of Aberdeen diocese. Return to Text

35. Temple (1894), p.21. Temple uses the old name of Gourdnes. Today, the lands are represented by Little Gourdas

36. MacGibbon and Ross (1887), p. 323. It is of interest that the authors added the alternative name for Gight Castle to their drawing - Formantine Castle (obviously an error for Formartine Castle). Return to Text

Bibliography.

Bain, J. (ed.) (1888) Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, Vol. iv, Edinburgh: by the Authority of the Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty’s Treasury. [CDS., iv.] https://archive.org/details/cu31924091754410/mode/2up

Barrow, G.W.S. (ed.) (1971) The Acts of William I, King of Scots, 1165-1214, Edinburgh, the University Press. [RRS., i.]

Cheyne, A.Y. (1931) The Cheyne Family in Scotland, Eastbourne: V.V. Sumfield.

Crawford, B. (2019) ‘Medieval Strathnaver’, in The Province of Strathnaver, John R. Baldwin (ed)., Edinburgh: the Scottish Society for Northern Studies. https://www.ssns.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/01_Crawford_Strathnaver_2000_pp_1-12.pdf

Duncan, A.A.M. (ed.) (1988) Regesta Regum Scottorum, Vol. v., The Acts of Robert I, King of Scots, 1306-1329, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [RRS., v.,]

Hume, John (1768) Plan of the Waterside Lands of Fyvie with the lands of Ardlogie, Woodhead and Fetterletter, and all the lands of Gight, (found in the Lower Rooms of Register House, 20th October, 1849). The National Records of Scotland (RHP11). Plan Of The Lands Of Fyvie And Surrounding Lands, Aberdeenshire | ScotlandsPlaces

Innes, Cosmo (ed.) (1845) Registrum Episcopatus Aberdonensis: ecclesie Aberdonensis: regesta que extant in unum collecta, Vol.1, Edinburgh: for the Spalding Club. [REA, i] https://ia802707.us.archive.org/15/items/registrumepisco01innegoog/registrumepisco01innegoog.pdf

Innes, Cosmo and Chalmers, Patrick (eds.) (1848) Liber S. Thome de Aberbrothoc: registrorum abbacie de Aberbrothoc, Volume 1, 1178-1329, Edinburgh: for the Bannatyne Club. [Lib. Arbroath, i] https://archive.org/details/libersthomedea0186arbruoft/mode/2up?ref=ol

Innes, Cosmo and Chalmers, Patrick (eds.) (1856) Liber S. Thome de Aberbrothoc: registrorum abbacie de Aberbrothoc, Volume 2, 1329-1536, Edinburgh: for the Bannatyne Club. [Lib. Arbroath, ii] https://archive.org/details/libersthomedea8602arbruoft/page/n7/mode/2up

MacGibbon, D. and Ross, T. (1887) The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland, from the twelfth to the eighteenth century, Volume 1, Edinburgh: David Douglas. https://ia800200.us.archive.org/14/items/castellateddomes01macguoft/castellateddomes01macguoft.pdf

McLeod, N.K. (1899) The Churches of Buchan and Notes by the Way, Aberdeen: A. & R. Milne.

New Statistical Account, Fyvie, County of Aberdeen, NSA, Vol. XII, 1845. (Contributed by the Rev John Manson, Minister of Fyvie.) [NSA] https://stataccscot.edina.ac.uk/static/statacc/dist/viewer/nsa-vol12-Parish_record_for_Fyvie_in_the_county_of_Aberdeen_in_volume_12_of_account_2/nsa-vol12-p315-parish-aberdeen-fyvie?search=Fyvie

Old Statistical Account, Fyvie, County of Aberdeen, OSA, Vol. IX, 1793. (Contributed by the Rev William Moir, Minister of Fyvie.) [OSA] https://stataccscot.edina.ac.uk/static/statacc/dist/viewer/osa-vol9-Parish_record_for_Fyvie_in_the_county_of_Aberdeen_in_volume_9_of_account_1/osa-vol9-p459-parish-aberdeen-fyvie?search=Fyvie

Pratt, John B. (1858) Buchan, Aberdeen: Lewis & James Smith. (Available at Google Books.)

Shead, Norman F. (2015) Scottish Episcopal Acta, Volume 1: the Twelfth Century, The Boydell Press for the Scottish History Society. [SEA]

Stuart, John & Burnett, George (eds.) Rotuli Scaccarii Regum Scotorum, Vol. 1, Edinburgh: by the Authority of the Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty’s Treasury. [Exchequer Rolls] https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=fuam4DKs1RoC&printsec=frontcover&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

Temple, William (1894) The Thanage of Fermartyn, Aberdeen: D. Wyllie & Son. https://archive.org/details/thanageoffermart00tempuoft/mode/2up

Thompson, K. (2014) The Monks of Tiron: A Monastic Community and Religious Reform in the Twelfth Century, Cambridge: University Press.

Watt, D.E.R. and Shead, N.F. (2001) The Heads of Religious Houses in Scotland from Twelfth to Sixteenth Centuries, Edinburgh: for the Scottish Records Society.